Canon Fodder, Episode 0: Watchmen with Billionaire Psycho

A Written Interview with the best of the best

This is Canon Fodder, Episode 0. For OPSEC purposes, my guest this week, The Billionaire Psycho, and I did a written interview. Billionaire Psycho (BP henceforth) is a Twitter poster, essayist and every writer’s best friend. His substack posts are some of the most insightful and detailed essays on the state of the modern world as well as the tools and tricks of writing.

When I had the idea for this project, I made a wish list of guests and what we could discuss. On top of mind was BP and Watchmen. We are both big fans of this comic (graphic novel for those who think comics are childish) because it separated itself from it’s contemporaries and the entire medium, in my opinion skyrocketing into the realm of literature and the greater canon. I’ll let BP explain why you should hold a similar opinion.

TR: Welcome, Billionaire Psycho. Thanks for Joining me.

BP: Honored by your friendship; inspired by your art.

TR: Question 0.5 Explain your relationship to the book. Edison Blake is an allusion to The Comedian, are you saying that the Billionaire Psycho [persona] is based on Eddie Blake?

BP: Subtle catch. Yes, I never intended anyone to pick up on this, but my FrogTwitter pseudonym “Edison Blake” is a literary allusion to Alan Moore’s Watchmen, and the character Eddie Blake, the Comedian.

Social media is a performance; our pseudonyms are symbolic masks which indicate the nature of our performance. Some digital avatars realize they’re participating in a circus — many never figure it out.

My mask was chosen to communicate my rage towards the status quo, and my contempt for social consensus.

Billionaire Psycho is a separate, overlapping joke, a Batman reference. Audiences cheer, clap, applaud in movie theaters for a fictional billionaire vigilante who brutalizes criminals. He represents a safe abstraction of heroism, a convenient morality play. Audiences give standing ovations to fictional outlaw heroes such as Dirty Harry, Wolverine, John Wick, Jack Reacher, Han Solo, Jack Sparrow, or Liam Neeson in the Taken franchise — everyone admires the lone samurai who dares to individually stand against the crimes of society, as long as the courage remains fictional. But in real life, the same crowds prefer comfort above justice; honor; morality; courage; patriotism; masculinity. Heroes who risk their lives to do what’s right, even when that requires rejecting social conventions — these men are prosecuted and frequently imprisoned. Crowds abandon men like Bernhard Goetz, Gary Plauché, Cain Velasquez, and Daniel Penny.

Even when the majority of civilians agree with a vigilante who risked his life to protect their community, civilians prefer to remain silent, stand aside, and allow a lone hero to be punished for protecting them.

So I chose a pseudonym which reflected that disconnect. The allusion to Eddie Blake, the Comedian, was chosen for similar reasons. Alan Moore’s Watchmen is a conspiracy thriller, designed around a murder mystery where a hidden villain is sneaking around murdering retired superheroes — Eddie Blake’s death provides the inciting incident which provokes the detective Rorschach to begin his investigation.

Rorschach scribbles down notes in his journal, which meditate upon the nostalgia of better times, the depravity of ordinary human civilization, Cold War tensions, and the imminent danger of nuclear Armageddon between America and the Soviet Union. This journal functions on another level as a frame story which unifies some of the otherwise scattered elements, vignettes, and episodes of the storyline together into a cohesive narrative.

Although the character Eddie Blake dies before the narrative commences, he is frequently referenced throughout the story with a series of flashbacks which explore the events and consequences of the Comedian’s life. He’s an extreme antihero: a violent, depraved monster who alienates the other superheroes… but he’s also a perceptive observer of human nature, and a fearless patriot who commits terrible crimes, and war crimes, in service of the American military.

What’s the significance of the name “Edison Blake”?

There’s three quotations from Alan Moore’s Watchmen which summarize who the Comedian is:

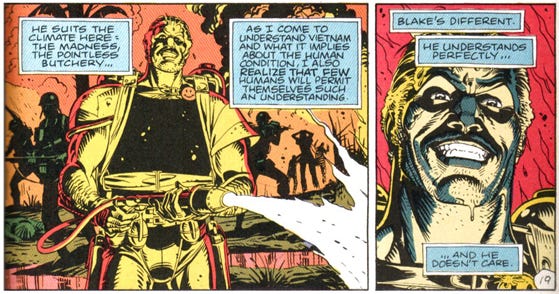

Doctor Manhattan comments about Eddie Blake during the Vietnam War, “Blake is interesting. I have never met anyone so deliberately amoral. He suits the climate here: the madness, the pointless butchery. As I come to understand Vietnam and what it implies about the human condition, I also realize that few humans will permit themselves such an understanding. Blake’s different. He understands perfectly… and he doesn’t care.”

Doctor Manhattan’s narration is juxtaposed against Eddie Blake using a flamethrower and smiling.

Another key line, concerning the fundamental contradictions and tensions of the American Empire, happens during a riot, when superheroes are beating up civilians. Nite Owl turns to the Comedian, and bemoans, “The country’s disintegrating! What’s happened to America?

Whatever happened to the American Dream?” And the Comedian laughs, and answers, “It came true — you’re looking at it.”

Last quote.

During captivity, Rorschach undergoes psychiatric examination, and he comments about his past friendships with the vigilante community, that the other superheroes were soft, naive, and cowardly, “No staying power. None of them. Except Comedian. Met him in 1966. Forceful personality. Didn’t care if people liked him. Uncompromising. Admired that. Of us all, he understood most. About world. About people. About society and what’s happening to it. Things everyone knows in gut. Things everyone too scared to face, too polite to talk about. He understood. Understood mankind’s capacity for horrors and never quit. Saw the world’s black underbelly and never surrendered. Once a man has seen, he can never turn his back on it. Never pretend it doesn’t exist. No matter who orders him to look the other way. We do not do this thing because it is permitted. We do it because we have to. We do it because we are compelled.”

Polite lies prop up dishonest systems.

The Comedian was willing to seek out truth, no matter how horrible it might be.

One of the “Redpilling” moments that happened in my life was when I saw footage of an November 2nd, 2018 interview on Good Morning America. Michael Strahan and the other hosts welcomed three obvious pedophiles, and a young boy (dressed as a girl) who was an ongoing victim of molestation, who danced under the title “Desmond is Amazing”. The abused child spoke with glassy, possibly drugged eyes.

Everyone in that crowded room cheered, smiled, and pretended this was wonderful. Michael Strahan is in many respects the ultimate embodiment of Black Excellence, aspirational masculinity, and achievement of the American Dream in this country. He is a 6’5”, 255-pound Hall of Fame defensive lineman who played for the New York Giants for fifteen consecutive years, accumulated an astonishing 854 tackles and 141.5 sacks, and is the current record holder for the most sacks by one player in a single NFL season (22.5 sacks). After sports, he transitioned to a thriving media career. He’s handsome, strong, confident, famous, well-spoken, popular, and rich — earning more than $76 million as a professional athlete, and tens of millions more as a television host.

So in many ways, Michael Strahan is the ideal American, the Platonic height of achievement in this country. It would’ve been easy for him to physically intervene, to save that abused child — but he sat back, and did nothing. And in that moment I realized, you need men who are willing to stare into the darkness of the abyss and to confront the worst horrors of this world.

Money, muscles, celebrity, strength, popularity, charisma, technology are not enough — what Michael Strahan lacked was moral courage. He was comfortable in his job, comfortable enough to interview pedophiles and an abused victim, then to look the other way.

Hatred, relentless obsession, and warriors who demand justice are necessary in order to protect civilization from the predators, parasites, and perverts which seek to prowl in the blind spots of polite society.

American bacha bazi is only possible because of widespread cowardice, effeminate convenience, and the communal abdication of protecting children from sexual deviants. This corruption is not something that happened overnight.

Nietzsche speaks of the “Death of God”, which is the disenchantment of the modern world — mankind’s technological ascent into an age of miracles, the mapping of unknown continents, the solutions of medicine, which have gradually eroded religious faith, or any trust in invisible supernatural forces and the divine Higher Powers that once provided meaning, purpose, and security in the promise of eternal paradise. Technology has exceeded religious promises, and has annihilated traditional beliefs. Communities suffer from an absence of spirituality, a religious vacuum.

The Indiana Jones franchise was popular because it focused on an archaeologist venturing into the shadows of history and stumbling across supernatural forces which remained strong in the modern world. It was about the Re-enchantment of a Disenchanted World.

The X-Files television franchise was popular for the same reason; beneath the paranoid detectives of an episodic police procedural, audiences are thrilled by the recurring tagline “The Truth is Out There”. Again, this represents Re-enchantment of a Disenchanted World. But the problems of postmodernism are a widespread, sublimated realization that civilization lacks any kind of shared meaning, purpose, or spiritual aim. The triumph of science has been marked by an abandonment of organized religion. Worse, religions seem to lack conviction, and now they appeal to the logic and persuasion of apologetics, rather than divine authority and the wrath of God.

Leftism has stared into this abyss of subjective truth, and it has broken their minds, resulting in a furious, resentful, and hysterical strain of nihilism.

Conservatives are mostly in denial that technology has obliterated traditional communities. “Go to church, get a job, find a wife, live in a rural wheatfield”... there’s a prevailing sentiment of willful ignorance and childish naivete. If you dig deeper, ideological entrenchment is a symptom of the overall lack of solutions, or political leadership. Tribes retreat into self-deception and rationalization of an unhappy status quo which seems impossible to solve.

In Watchmen, the characters Rorschach and the Comedian are fixated on the meaning of truth, and the responsibility to confront the worst darkness of humanity.

Eddie Blake spoke to me as an amoral symbol, someone who was willing to be a monster to triumph in a monstrous world.

This resonated with the final passage of Bronze Age Mindset, written by Bronze Age Pervert, about needing men with the hatred and strength to descend into the criminal underworld to bring about a superior future:

“Unfortunately many pay no attention at all to these two ways of “discipline,” but instead are concerned only with the public image of their virtue or goodness. There’s next to no good in that. And the right has hurt itself considerably by the adoption of this kind of Phariseeism. I give you an example of what I mean: many of the intelligence agencies are populated with Mormons. These men are chosen for their upright moral character, the fact that they pass lie detector tests, that they’re not easily compromised, and so on…all qualities that make for bad spies. To be effective in this world you must be very well-acquainted with the underworld, with criminal life, with junkies, dealers, prostitutes, gamblers, with the perviest of pervs. And this is what I mean by the great down-going. To gain a true hold on the foundations of this trash-world, a certain group among the right will have to descend in this inferno. I am firmly convinced that this is the key to overturning everything that is corrupt, and the path to the great purgation. I imagine a network of brothels and gambling houses around the world, production of porn videos, and a complete penetration of the world of vice. Yes, to ensnare, to compromise, to corrupt, and above all to observe and to know their secrets. To descend into a floating world of complete vice, and even to engage in it—as you must if you are to thrive in this world—while keeping your head and keeping in focus the fire of your aim…isn’t this a great and very difficult achievement? This path must be only for very few, very few are suited to it. But these few are to be among the greatest of the coming generation. This brotherhood will work instead to intensify vice, to stir up demonic passions, to sow total confusion in the heart of the beast.”

—Bronze Age Pervert, Bronze Age Mindset

TR: Question 1. The medium of Comic books has been around since at least the 1930s, and the pulps before them were equally popular and told similar stories. It is clear that Watchmen stands apart from the rest, so much so that people consider it literature. What about Watchmen is so captivating?

BP: Alan Moore’s Watchmen is a layered, multifaceted narrative. It functions like a Rorschach test. Everyone who reads Watchmen gravitates towards a different aspect of the story. And I wouldn’t even say that Watchmen is necessarily a fun, enjoyable read — the narrative is relentlessly bleak, cynical, nihilistic, grim, and tragic, with only a few happy moments. Nonetheless, this is a story of technical sophistication, complexity, and philosophical beauty which ascends to the highest expression of what the comics medium is capable of.

One example is Issue Five: “Fearful Symmetry”, which is a 28-page comic where every page, and every panel is designed to be perfectly symmetrical. That kind of craftsmanship requires an exhausting level of attention, precision, vision, and effort.

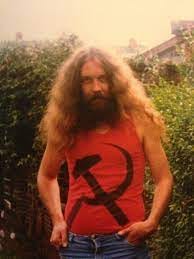

The vast majority of novels, movies, comics, and television franchises never attempt anything of comparable scope and ambition. Alan Moore was exhausted by the meticulous attention to detail he devoted to Watchmen, and after finishing this series, he never wrote another project with the same level of manic, rigidly disciplined obsession.

Let’s consider some math.

A standard comic book contains twenty-two pages of art and story, accompanied by ten pages of advertising. The actual script written by the author, then given to the illustrator, will usually average between one to two pages per comic page. So for a normal twenty-two page comic book, a standard script might end up around thirty to thirty-five pages.

Alan Moore’s scripts averaged closer between eighty to one hundred pages per comic issue. The twelve-issue miniseries Watchmen required more than one thousand pages of script. If you examine a photograph of Alan Moore’s original scripts, every line is crammed with detail, there’s zero spacing or indentation — the scripts look like they were written by a lunatic trapped in an asylum (and maybe they were).

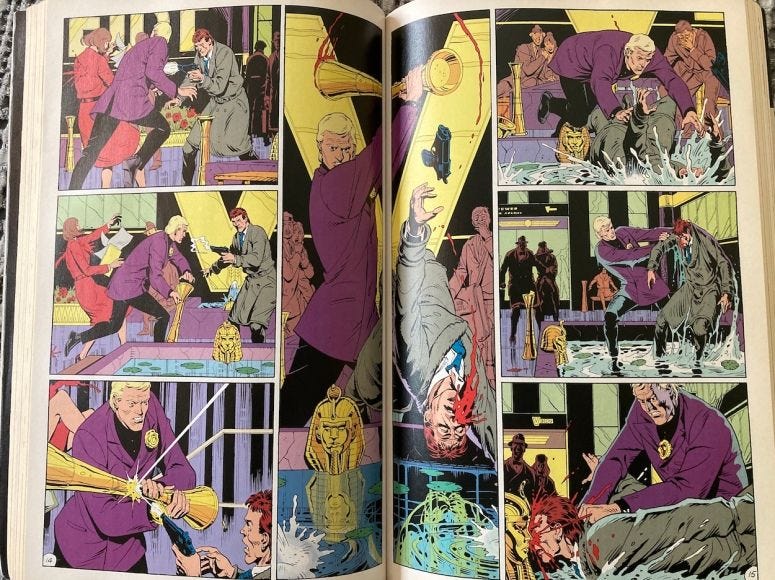

In addition to flowery prose, witty captions, and fast-paced dialogue, Alan Moore’s scripts delved into extreme detail about visual composition, camera angles, character expressions and poses, colors, Easter Eggs, and the relationship between the foreground and background — which was crucial information for the illustrator Dave Gibbons, even though those instructions are never seen by the comic’s audience.

Watchmen also operated based on a nine-panel grid, which split each page into nine visual images, complemented by text captions. The industry standard is that ordinary comics will use three to five panels per page, with an occasional full-page spread depicting a dramatic, cinematic visual.

Nine panels increased how much text could be inserted into the captions of each page, and also allowed a flashback technique of shifting between intercutting colored panels which signified separate timelines. In one page, Alan Moore’s storyline might cut between as many as four different time periods: the nine-panel grid might alternate between Timeline A, Timeline B, Timeline A, Timeline C, Timeline B, Timeline A, Timeline D, Timeline A, Timeline B. Obviously this nonlinear presentation of fictional events threatened to confuse audiences. Visual cues, distinct costumes specific to each time period, and the use of color-coded backgrounds served to provide sharp clarity.

The strength of nonlinear storytelling is that events can be arranged to serve the narrative’s theme, rather than being constrained by the mechanical necessities of exposition, plot, and suspense. Events are chosen to contrast, stress, and reveal the true nature of each character.

A difference in degree is a difference in kind.

We can measure in mathematical terms the increased complexity of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, contrasted against the typical monthly comic. Alan Moore’s peers weren’t playing the same game.

Complexity by itself is a poor measure of quality. Perhaps in most instances, excess complexity is in fact a negative indicator. But Watchmen achieved a narrative density, depth, and texture which is unparalleled.

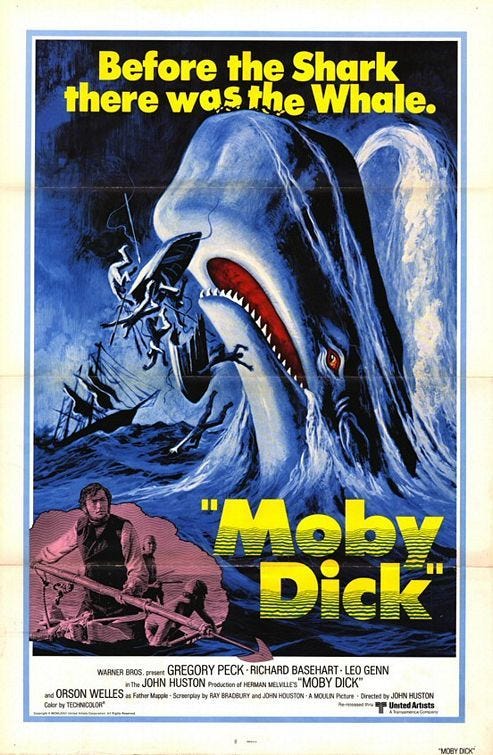

In various interviews, Alan Moore explains that he wrote Watchmen with the ambition of constructing a franchise with the same kind of complexity and philosophical texture as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

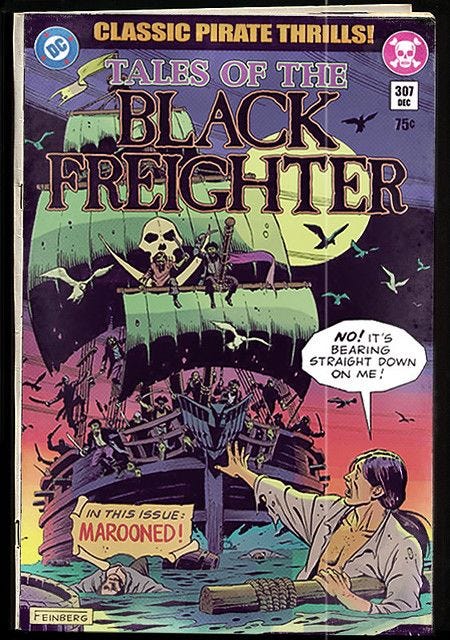

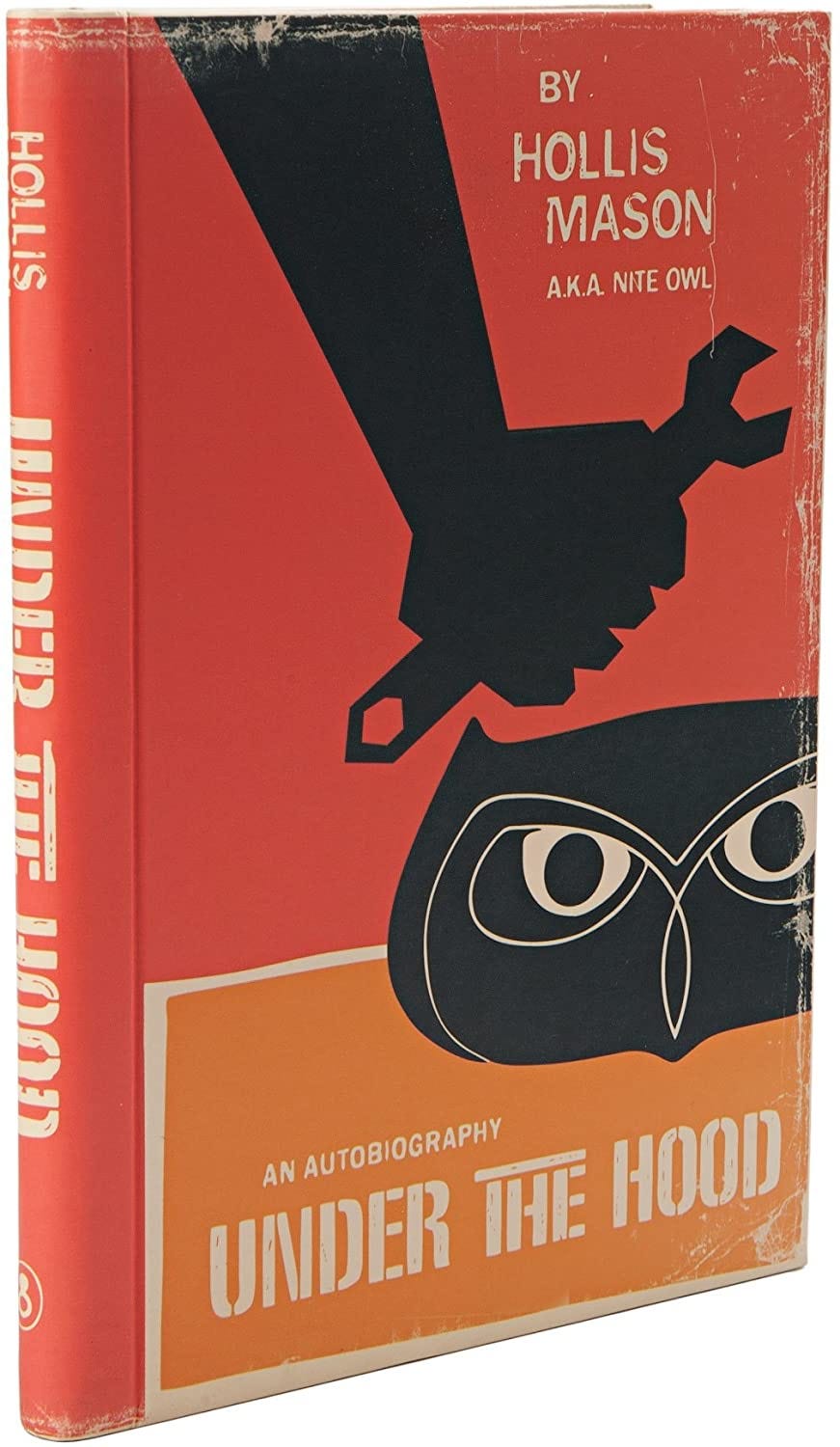

Ironically, advertisers didn’t want to promote their products with Watchmen, because they expected the comic to be a failure. As a result, the ten pages that ordinarily were dedicated to monthly advertisements were now blank spaces that needed to be filled. Alan Moore responded to this abrupt, unexpected problem by creating vast amounts of prose content to bookend each issue, which transformed Watchmen into an epistolary novel that featured various documents that added texture and backstory to the fictional setting’s worldbuilding. This includes “Under the Hood”, a fictional confessional autobiography from a retired superhero selling his memoirs, “Doctor Manhattan: Super-powers and the Superpowers by Professor Milton Glass”, which analyzes the impact of superheroes on the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War, “A Man on Fifteen Dead Men’s Chests”, which explains the fictional history of the creators of the Tales of the Black Freighter pirate comic, the psychiatric records of Rorschach and his alter-ego Walter Kovacs, “Blood from the Shoulder of Palas” which is a philosophical ornithology report written by Nite Owl’s alter-ego Daniel Dreiberg, a newspaper issue of the Fascist publication New Frontiersman, nostalgic pin-ups of the retired sex symbol Sally Jupiter, a series of internal memos conducting the business of Ozymandias’s corporate business empire, and finally, “After the Masquerade”, which is a prestige journalist’s interview of Ozymandias in the style of a Vanity Fair or Sports Illustrated cover article. These epistolary documents are fun little bonus material, small toys and gifts to the audience.

None of them are necessary material to understand the main storyline. Each epistolary document is designed as a thematic expansion of the monthly issue it’s paired with, and functions to indirectly, obliquely expand the world of Watchmen with a particular focus on the viewpoint character who stars in that month’s issue. The overall complexity is dazzling.

The nine-panel grid, nonlinear storytelling, massively detailed scripts, and ten pages of bonus epistolary documents are four mechanical techniques which separate Alan Moore’s Watchmen from any competing comic. Nobody else in professional comics attempts to use the combination of these four techniques, because it’s a massive amount of excess labor that serves a thankless, ornamental role. The accelerated schedule of a monthly ongoing comic makes this level of complexity and obsessive preparation an expensive, impractical, and unfeasible standard for any creator to pursue. Indeed, Alan Moore spent months preparing for this twelve-issue miniseries, he fell behind during the publication (which caused delays to the planned schedule), and he was exhausted in the aftermath of his triumphant conclusion of the series.

The workload is prohibitive, and daunting.

Alan Moore’s Watchmen was designed specifically to be reread by fans, who would feel the satisfaction of discovering subtle narrative elements that were inserted into the structure of the comic.

In a 2009 interview, Alan Moore elaborated on his technical intentions:

“I’d written Watchmen expressly because, on one level, I was a bit tired of this easy analogy between comics and movies that some of the most intelligent people in my medium still trot out without really thinking about. I mean, undoubtedly, someone who understands cinematic storytelling is going to be a better comic writer or artist than somebody who doesn’t. Will Eisner went to see Citizen Kane thirty times. That’s all fine. The problem is that if comics are always seen in terms of cinema, then ultimately they can only be a film that doesn’t move and doesn’t have a soundtrack. With Watchmen, I wanted to find those things which were unfilmable, that could only be done in a comic. So, for example, we had split-level narratives with a little kid reading a comic book, a newsvendor going into a rightwing rant next to him, and something else going on in the background in captions, all at the same time and interrelated. These are the things you can do in a comic, but not even the greatest director in the world could manage, not even if they cram the backgrounds with sight gags, like Terry Gilliam, who would in many ways have been the best director for Watchmen. It’s not the same as reading a comic, where you can flip back a few pages and look at a detail that Dave Gibbons put into the background to see if it really connects up with that image that you remember from a chapter or so back.”

Author Gene Wolfe postulates, “My definition of good literature is that which can be read by an educated reader, and reread with increased pleasure.”

Beyond any doubt, Watchmen achieves that goal.

TR: Question 1.5 Do you consider Watchmen literature and where do you put it in the Western Canon if there is a spot for it?

BP: Literature reveals the human condition.

Watchmen is one of the most honest interrogations, and illuminations, of the fantasies and nightmares; neuroses and anxieties of the Boomer liberal mind — it’s a keen analysis of the dysfunctional worldview which built the modern world.

The past century has played out in the shadow of enormous historical tragedies, and the desire to avoid repeating the mistakes of World War One, World War Two, the gulags of the Soviet Union, the Khmer Rouge, and the Chinese famines and persecutions of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. Death and misery occurred on a scale which is impossible for the human mind to comprehend.

To escape tragedy, war, famine, genocide, and nuclear Armageddon, the American Empire retreated into the politics of SEDATION. Consumerism kept citizens numb, comfortable, and distracted in order to prevent World War Three, or nuclear Mutually Assured Destruction. Total catastrophe felt inevitable, and unavoidable.

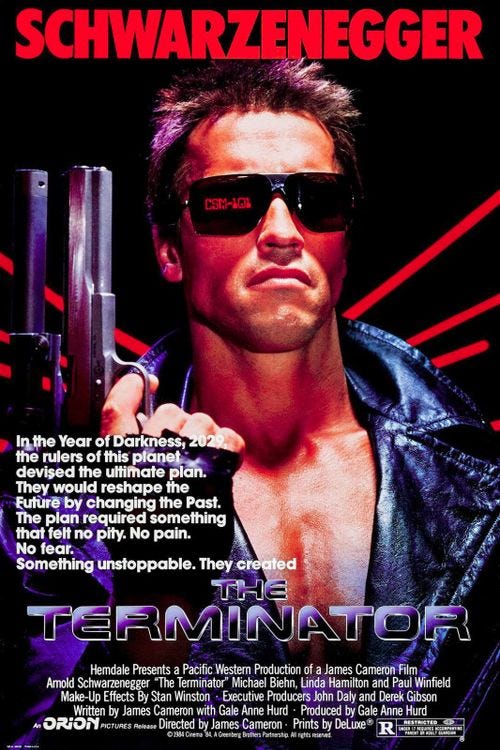

Boomer psychology reflects the paranoia and anxiety of a Millenarian Cult, which is civilization upon the precipice of instant annihilation. James Cameron’s Terminator is one of my favorite examples of nuclear paranoia, and how the dominant zeitgeist was fueled by the nightmare of technology too dangerous for humanity to control. Sort of this Promethean anxiety, an eternal mythological fear of Icarus flying too high, Pandora opening her Box, Frankenstein destroying his creator, Adam and Eve tasting from the Tree of Knowledge.

Almost every facet of contemporary America is designed to collapse as soon as the Boomers die off in the 2030s: bridges, railroads, power grids, pensions, the stock market, the housing bubble, America’s national debt, and the college credentialing system.

Fear of Nuclear Armageddon simultaneously provided the motivation, justification, and rationalization of the Boomer lifestyle of excessive frontloaded consumption paired with backloaded debt, unsustainable nihilistic materialism, and deferred maintenance of decaying infrastructure.

But it makes sense if you think about it from the Boomer perspective: If you expect the world to end tomorrow, why not “Live today as if it’s your last?” Unfortunately that mindset neglects responsible future investment.

A 1995 interview of famous British novelist Martin Amis, entitled “The Prose and Cons of Martin Amis”, offers some clarity regarding the fears and fantasies of the Boomer generation:

Martin Amis: “This will sound old hat now, but the big question of the second half of this century was, What are we going to do with nuclear weapons? Now that we've got out of the emotional idea that it could all end tomorrow, we can look at other things. That's a success story, and an evolutionary development of huge significance. We can now look at other things.”

Graham Fuller: “Do you feel your recent books have been written in the shadow of the millennium?”

Martin Amis: “Yes, very much. London Fields is proclaimedly about the end of the millennium. You do feel that history is approaching a climax and that all over the world one is seeing the classical symptoms of millenarian anxiety and fever: fundamentalism, strange weather, et cetera. I think 1999 will be the year of behaving strangely. People behave strangely at the end of centuries, let alone at the end of millennia. And the world is certainly ripe for it, isn't it?”

—Graham Fuller, The Prose and Cons of Martin Amis

Sometimes foreigners can observe, study, and understand an empire better than native residents. Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” is the classic example.

Alan Moore grew up in blue-collar poverty, living in the wreckage of the British Empire, shrunken down from global dominion to a landlocked island. His entire childhood was spent in a vassal state of the ascendant American Empire, and the euphoria of the Reagan years felt sinister and frightening from his perspective — a false confidence which couldn’t last.

Since the aftermath of World War Two, and the British Empire’s quiet retreat from geopolitics, British politics has been consumed by a sublimated despair: There are no solutions, only scapegoats. The loss of empire has inflicted a terrible wave of recessions and self-cannibalization onto Britain, with large swaths of the island nation trapped in hopeless downward mobility, and nobody in British politics is ever willing to confront the truth that the surrender of their naval military Empire necessitates a lower standard of living.

Britain developed a bold artistic subculture during these decades, a vibrant punk scene which scorned aristocracy and traditional English virtues, fueled by the rage and resentment of life in a shattered empire. Angry young men felt betrayed and embittered that the promises of previous generations had resulted in disappointment.

Alan Moore’s Watchmen offers a unique perspective on the zeitgeist of the global American Empire, delivered from the perspective of a conquered vassal state.

TR: Question 2. There is a lot of debate about Alan Moore, especially his comments about Rorschach. Some say he is a crypto-rightist while others say that he wrote a great character by accident. I take it that you land somewhere in between, but I’d like to get your thoughts on Rorschach and maybe “Right Wing” characters in general.

BP: Alan Moore is a brilliant artist, and an unapologetic Leftist.

Everyone forgets where Rorschach came from, and why Alan Moore wrote Watchmen, which on some level is a measure of the franchise’s success — Watchmen has become a hyperreal object; celebrated by critics, beloved by fans, but alienated from its humble origins. The fictional story world feels real and alive, which is some of the highest praise you can bestow upon any narrative.

The contemporary dominance of Marvel and DC Comics has crowded out the history of the past century, and the contributions of their now-defunct competitors.

In the 1980s, a once-proud comics publisher named Charlton Comics was bleeding out and gasping for breath. They were so broke that their printing presses no longer worked, and they couldn’t afford to purchase replacements for the mechanized presses necessary to print their own comics. In desperation, in 1983 Charlton Comics sold copyright ownership of many of their most popular characters to rival publisher DC Comics, at a price of $5,000 per character. This roster of characters acquired by DC Comics included Blue Beetle, Captain Atom, Thunderbolt, The Question, Nightshade, and Peacemaker. The company stopped publishing in 1984, and declared bankruptcy in 1985.

DC Comics was eager to capitalize on their newly-acquired superhero characters, so they turned to a British rising star named Alan Moore and asked him to helm the product launch with a miniseries storyline that featured the Charlton Comics heroes. The intent was to introduce the new heroes to DC’s main shared universe.

At the time, Alan Moore was experiencing his first real taste of success. He had taken over the struggling Swamp Thing comic series, saved the franchise from cancellation, and established significant credibility as a visionary writer with bold, insightful takes on stale material. Editors at DC Comics identified him as one of their best new hires.

In a 1988 retrospective, Alan Moore explains the origins of Watchmen:

“It all began innocently enough, the initial impulse coagulating from a number of seemingly innocuous sources. Firstly, DC Comics were eager for me to write something else for them in addition to the monthly SWAMP THING. For my part, having taken SWAMP THING over from another writer “on the run” as it were, I’d been forced to learn how to write full-length comic books at a breathless pace that leaves no time for proper planning or contemplation. Having formulated a few ideas about the possibilities of the American comic book during that heady, forty-issue rush, I was anxious to try them out in a new title that could be styled and designed from the ground upwards, and thus took up DC’s offer with little prompting.

…

The final element was the plot and substance of the work itself, born from a lot of half-remembered pre-professional fantasies about how I’d write a comic book, given half a chance. In its simplest form, the notion was simply to take over a whole comic book continuity and all the characters in it, so that one writer could document the entire world without worrying about how his plans could be fitted in with the creators of the other titles his characters were currently appearing in. Regular comics, with their insistence upon rigid, cross-title continuity, present a lot of annoying limitations to the creator. The worst of these is that nothing can ever happen in an individual story that has any lasting effect on the world, since it is the same world inhabited by every other character in the company’s line. Having a whole cast of characters in a self-contained world would solve these difficulties… This, restricted to idle fanboy musing as it was, had no special significance, save that it was fairly easy to make the conceptual leap to the characters of the defunct Charlton comics line once I heard that DC had acquired the rights to them.

…

One thing that becomes clear upon rereading these early notes is that despite its eccentric flourishes of style and character, what we had here was a fairly straightforward superhero story. Any superheroes would have done.”

—Alan Moore

So, DC Comics acquired popular characters as Charlton Comics slid deeper in debt, plunging towards insolvency and liquidation. Around the same time, Alan Moore’s career was beginning to catch fire. Editors at DC Comics asked Alan Moore to propose a miniseries starring their new heroes (Blue Beetle, Captain Atom, Thunderbolt, The Question, Nightshade, and Peacemaker), and he agreed.

Alan Moore returned with the proposal for Watchmen, which he submitted to editor Dick Giordano. DC Comics loved Alan Moore’s proposal, but they were horrified by the realization that his miniseries would scar, cripple, and permanently tarnish various members of the newly acquired Charlton Comics roster. Editors suggested that Alan Moore invent a new ensemble of heroes, living in a separate, self-contained universe, so that he could write his story without damaging the value of DC Comics’s intellectual property.

Eventually Alan Moore realized he could construct familiar characters who resembled the Charlton Comics superheroes of his original proposal.

And so the Charlton superheroes became the Watchmen:

● Blue Beetle (Nite Owl)

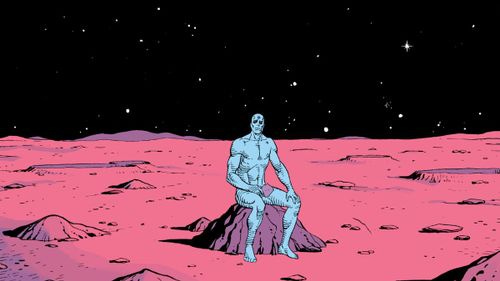

● Captain Atom (Doctor Manhattan)

● Thunderbolt (Ozymandias)

● The Question (Rorschach)

● Nightshade (Silk Spectre)

● Peacemaker (Comedian)

That’s a long, convoluted, and unconventional origin story.

Rorschach was designed as an imitation of Steve Ditko’s The Question, and influenced by another Steve Ditko creation, a lesser-known superhero named Mr. A.

The Question is a paranoid conspiracy theorist, and a fervent adherent of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism belief system. He is a brutal vigilante who perceives the world in rigid, draconian, unforgiving terms — and Alan Moore did a beautiful job of honoring Steve Ditko’s enthusiasm for the principles of Ayn Rand.

In his original proposal for Watchmen, Alan Moore wrote,

“When all the superheroes retired in 1977, The Question was the only exception. The Question is not in the slightest bit concerned with the law. He is concerned with Truth and Morality, and if that means breaking corrupt laws that only exist because of the actions of dissident pressure groups and minorities, then he will break them without thinking about it. Not, however, without consequence. The Question is currently wanted by the police on numerous charges, including seven counts of murder.

The way I see The Question, he is such an extreme character that even hard-line right wingers would feel nervous about his attitudes and actions. The thing is, in order to present the character fairly, I will have to make those views completely logical and heartfelt so as to not present him as a parody of right-wing attitudes as seen by a left-winger. Depending on which way you look at him, The Question is either the one incorruptible force at large in a world of eroded morals and values, or he is a dangerous and near-psychotic sociopath who kills without compassion or regard for legal niceties.

I suppose what I want to do with the character is to keep him as true as possible to the quintessential Steve Ditko character and philosophy. Now, while I’ve always found Steve Ditko’s expressed political opinions to be strange and possibly dangerous, I have a huge amount of admiration for anybody who is prepared to take an unpopular position simply because they happen to believe it’s morally right. Morals today are at a premium, whether you happen to agree with them or not. On top of this, I have the greatest possible regard for Steve Ditko as an artist and wouldn’t want to portray his characters falsely or inaccurately.”

—Alan Moore

Alan Moore’s original proposal for Watchmen was rejected. He submitted a modified proposal which was then accepted. In the second version, Alan Moore expanded the character,

“Rorschach is the replacement for The Question, and draws his name from the famous psychiatrist’s blot-test.

…

The black-and-white motif ties in with the character’s very hard-edged moral philosophy, and is also used by the character himself as a metaphor for the ambiguity of life. Each man must read his own fate into the pictures conjured by the neutral Rorschach blot, and judge himself accordingly. Rorschach’s secret identity is unusual. He poses as a placard-toting religious fanatic and lives in a seedy one-room apartment that is a horrific and squalid mess. He eats tinned food cold straight out of the can and only sleeps about four hours every night. He’s a man on edge in more respects that one, and his ‘Edge of the World Is Nigh’ placards will take on a more solemn significance as the story progresses and the world in the strip moves closer to all-out thermonuclear war.

…

He is an obsessed character who will do absolutely anything in pursuit of his own rigid moral code, save contradict his own beliefs… He is implacable, ruthless, and quite unpredictable.”

—Alan Moore

The genius of Alan Moore’s Watchmen shines brightest in psychological realism, which is the depth and complexity of his characters. Similar to Game of Thrones, Watchmen features a world of moral ambiguity. Every member of the ensemble cast is a mixture of virtues and vices; strengths and flaws; ambitions and insecurities. In public speeches, Alan Moore lays out a theory of how to write realistic, sympathetic, and dramatically satisfying heroes. He explains that there are one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional characters. One-dimensional characters are either heroes or villains, they are instantly recognizable in terms of a childish black-and-white morality, and when you know whether they are good or bad, everything they will do becomes predictable.

Two-dimensional characters are heroes with cosmetic flaws. A teenage hero might argue with his girlfriend. A wife might disagree with her husband. Heroes are endowed with minor imperfections, insecurities, and interpersonal dramatic conflict with their long-term allies in order to add texture and intrigue to the episodic narrative.

Three-dimensional characters are fully realized humans, a mixture of good and bad… never completely predictable because they are torn between competing impulses. Flawed heroes and sympathetic villains bring passion, danger, and volatility to what might otherwise be a formulaic storyline.

In a 1984 interview, Alan Moore confesses,

“I’m not so much interested in coming to a conclusion as in examining the problem thoroughly. I’ve got a strong dislike of what I’ve referred to as “The Baby Bird School of Comic-Book Moralizing” — where the writer gets the audience to sit there with their beaks open and feeds them. “Here’s what you should think about nuclear war.” We might be good comics writers, but we don’t necessarily know anything about morality, human nature, and politics.”

And in a 1988 interview celebrating the success of Watchmen, Alan Moore strikes the same theme:

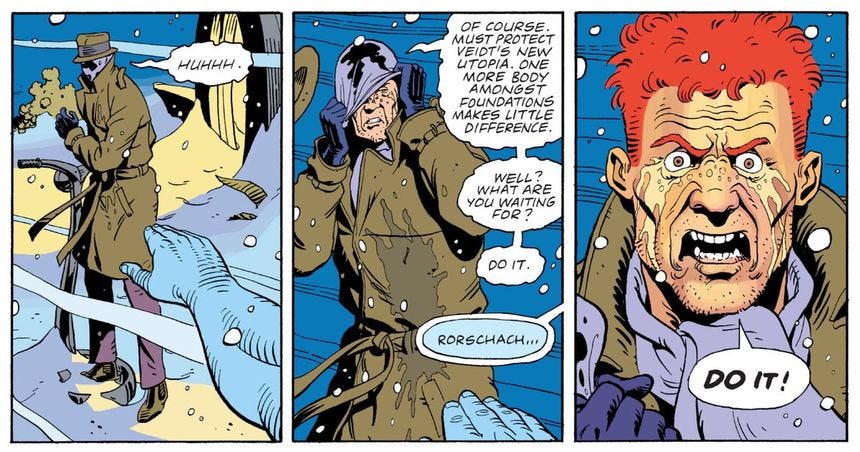

“Q: I’d like to ask you some questions about the themes of Watchmen. It seems that the book is finally about Rorschach and Ozymandias in terms of their centrality to the narrative, and they are rather archetypal figures in their connections to certain types of protagonists in literature. Rorschach seems like this wretched, acted-upon character who figures prominently in modern art from [Georg Büchner’s] Woyzek to [Alfred Hitchcock’s] Psycho, while Ozymandias is a more classical hero, a symbol of empire and a person in absolute control of his destiny.”

Alan Moore: “You could see them in those terms, particularly with the final confrontation, if you like, although it’s not much of a confrontation. The denouement, with what happens to Rorschach and what happens to Veidt, might support that interpretation, I suppose. What we were trying to do with Watchmen was primarily to avoid a sort of baby-bird school of moralizing where the readers sit with their beaks open as they are force-fed certain predigested morals by the writer. We wanted to avoid the type of adventure fiction where the character who wins all the fights ends up with the white hat and is seen as the hero. Instead, we invented six characters, each of whom has a radically different view of the world. Rorschach has a view which is very black but essentially moral.

The Comedian has a view which is also black but essentially amoral. Dr. Manhattan has his own peculiar view of the world, which could also be seen as valid. Indeed, according to some readings of Watchmen, it might be possible to construe Adrian Veidt as the hero. What I wanted to do was to give each of the characters, including the ones I politically disagree with — perhaps especially the ones I politically disagree with — a depth that would make it feasible that these were real, plausible individuals.

I especially wanted to avoid making Rorschach and the Comedian foils for my own moral opinions. I wanted these characters to have the kind of integrity to cause the reader actually to sit down and make some moral decisions. We wanted to present the reader with a variety of worldviews and some hard choices to make.

…

Certainly the book is about power, but it’s about different manifestations of power… It was an investigation of the different uses of power, and the effects of power.”

—Alan Moore

All of this theory is very grandiose. It’s abstract and impractical.

The execution relies on moral ambiguity in how plots are resolved. Even when Rorschach dies, he believes he is winning a symbolic moral victory.

Every character in Watchmen believes his worldview is correct, and that he is the hero of the story.

Each of the six core characters represents a different philosophy, and a different form of power:

● Ozymandias (utilitarianism/Leftism, power of genius, money, and corporate resources)

● Rorschach (existential despair, power of obsession)

● Comedian (nihilistic absurdity, power of the military)

● Doctor Manhattan (atheistic quantum mechanics, power of Science and nuclear bombs)

● Nite Owl (ordinary man, power of technological ingenuity)

● Silk Spectre (ennui and distrust or resentment of of the extraordinary, power of sexuality)

This is an imprecise definition, a clumsy attempt to summarize deep, complex characters in useful terms. Don’t take it too seriously.

Keep in mind these philosophical arguments were written with deliberate ambiguity, and intended to express themselves obliquely.

Nite Owl is designed as the control group, the ordinary man who contrasts against the rest of the ensemble. In his original proposal for the series, Alan Moore explains,

“As you may have begun to notice, the characters I’ve mentioned so far [Doctor Manhattan and Ozymandias] are both pretty weird psychologically speaking, at least compared to human terms of reference.

The Blue Beetle, on the other hand, is the most human of the entire bunch, and he will exist in this book as a standard against which the other characters are measured. If all the characters are weird and unusual, none of them will stand out. Thus, I see the Blue Beetle as being just an ordinary man who does extraordinary things, who sometimes makes mistakes or is uncertain about what’s going on, and who sometimes feels afraid.”

—Alan Moore

So, to summarize these interconnected observations:

Alan Moore designed Rorschach as a faithful homage to Steve Ditko’s The Question, and this hero Rorschach embodied the morality of an Ayn Rand novel. The psychology and philosophy of Watchmen is endlessly fascinating because of intentional ambiguity, and the careful design which stressed that every character believed fervently in his particular worldview, supported by a logical, persuasive rationale.

It’s a game, readers are incentivized to search for clues, and that vicarious psychological interaction has inspired a loyal, obsessive fanbase.

Watchmen refuses to provide the audience with explicit answers.

Audiences are forced to dig.

TR:Question 2.5. A more general question about British Comic book writers. Moore was the first and probably pinnacle writer from Great Britain, but after him you have Neil Gaiman, who has seen a lot of success as well as Grant Morrison, who is well respected in his medium, if not well known outside of it. Is there a secret sauce in GB? What role does Heavy Metal Magazine play?

BP: Britain operated as a farm system for America.

Ambitious young men would build a reputation in the British minor leagues, gaining momentum, aiming to hit escape velocity, when they would be scouted and recruited by a big American publisher to play in the major leagues. The same process repeats in the American major leagues, where bestselling comics authors lack creative ownership and long-term revenue-sharing of a franchise like Batman, Justice League, or Spider-Man, so authors and illustrators would commit several years to writing a famous property that earned a steady paycheck while building a dedicated audience under the umbrella of an incumbent publisher, dreaming of the day they could split off and create their own lucrative franchise in the mold of Hellboy, Spawn, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or The Walking Dead.

Neil Gaiman started in Britain, rose to America, accumulated a loyal fanbase and became a literary superstar while he was working for a larger company, and then he split off to write novels where he was keeping a larger percentage of revenue. Talent pipelines require cultural infrastructure, with an experimental, underground subculture feeding into a larger network with massive distribution.

Mainstream behemoths need vibrant subcultures to fuel innovation.

The same dynamic plays out in other industries.

Tech companies regularly acquire smaller startups to seize control of some brilliant new innovation which is pivotal to gaining, or retaining market share.

Disney acquired Marvel, Lucasfilm, and Pixar to remain relevant, because Disney had lost the ability to launch their own gorgeous, beloved animated films. Personnel is policy.

Great Men move history.

From a distance, casual observers evaluate literature, cinema, television, comics in terms of their market capitalization — how many billions of dollars of products are being sold, purchased, designed, advertised, discarded on an annual basis. Up close, these are small industries, small networks of people, and the storytelling business runs on personal relationships. The industry is consolidated into a handful of gigantic conglomerates, which operate through bewildering labyrinths of subsidiaries. Only a handful of executives and editors are making decisions. Most of them are incompetent herd animals, focused on self-preservation and a desire to play it safe by picking proven winners, popular trends, infinite sequels, and incumbent franchises.

New talent is forced to bleed and claw in order to gain a foothold in the industry. There’s a lack of coaching for young writers, artists, dreamers who are unpolished but demonstrate brilliance, passion, insight, and obvious potential. Amateurs are expected to teach themselves professionalism, which is a long, hard road.

There’s a lot of nepotism, which is not necessarily a bad thing, because the upside is that friendship and loyalty can often be rewarded with long-term careers. In film, television, literary publishing, and comics, executives tend to be incompetent managerial functionaries who specialize more in finance, marketing, promotion, and distribution… they don’t understand art on a deep level. They can’t scout talent on a reliable basis. When you talk to them, there’s this blithe smugness and a lack of curiosity — a serene, habitual overconfidence which is sporadically punctured by this nauseating fear that they have no idea how to evaluate quality without credentials, recommendations, or personal friendships, and the unsettling realization that they’re just pretending to be experts.

Every field has obstacles; art is obstructed by distracted, stressed gatekeepers who are too busy to develop young talent, and therefore never develop the skill of properly coaching ambitious, idiosyncratic visionaries to realize their imagination.

If you read various biographies chronicling the history of the entertainment industry’s biggest winners — Stephen King, J. K. Rowling, George R. R. Martin, George Lucas, Neil Gaiman, Dan Brown, David Baldacci, Christopher Nolan, James Cameron, Sylvester Stallone, Bill Willingham, Taylor Sheridan, Francis Ford Coppola, John Grisham, John Lasseter, Quentin Tarantino, Robert Kirkman — there’s an unbelievable amount of rejection.

Some examples:

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone did an initial print run of 500 copies, and was not expected to be profitable.

Titanic was expected to flop.

Star Wars: A New Hope was expected to flop; executives were canceling film production during the final weeks, and Alan Ladd Jr. had to fight with the studio to finance the final week of shooting. Avatar was expected to lose money (even after James Cameron had filmed Terminator, Aliens, True Lies, and Titanic), to the point where 20th Century Fox canceled the project, and James Cameron responded by threatening to bring the film to Disney, which motivated 20th Century Fox to recommit to the project.

Christopher Nolan filmed Memento, nobody wanted to distribute it for a year, and then Steven Soderbergh intervened to raise the necessary cash.

Francis Ford Coppola was miserable during the film production of The Godfather because the studio executives of Paramount Pictures kept threatening to fire him, challenging his budget, and undercutting his creative decisions.

Harvey Weinstein gave Peter Jackson a three week ultimatum to transfer production of Lord of the Rings to a new studio, or lose control of the franchise.

The list goes on.

Most artists lack business sense, and are typically guided towards failure by the gatekeepers who initially sign them.

All of this is a major source of frustration for young artists, writers, novelists, screenwriters, and film directors — but the main problem is expectations. Artists expect to be supported, they expect their careers to be carefully shepherded through a perilous marketplace by an experienced professional guide (an agent, an editor, or a film producer) who is empowered by deep pockets, institutional credibility, and loyal, transparent relationships with trusted distributors.

From the perspective of a novelist, screenwriter, comic author, or film director, it seems only logical and self-evident that their first professional contract will be viewed as a serious investment by the organization who pays them.

But from the vantage point of a book publisher, film producer, Hollywood studio, television network, or comics publisher, art is an unpredictable business, and organizations are incentivized to hedge their risk in the aggregate by signing a large roster of clients, and then gambling haphazardly with their careers, trusting in the statistical probability of power-law distributions that One Big Winner will emerge from the chaos.

Authors can only commit to one, two, or maybe three projects at a time.

For example, during a three-month period in 1983, James Cameron wrote screenplays for The Terminator, Aliens, and Rambo: First Blood at the same time. This was incredibly difficult, grueling, and stressful — James Cameron missed his initial deadline, and was forced to negotiate an extension.

Studios and publishers are always considering new projects, fresh proposals, while at the same time developing sequels, promoting ongoing franchises, and working with trusted, proven artists who have built a reputation for reliable, quality work.

That’s the disconnect.

Individuals can only live one life; institutions can hire multitudes. Perverse incentives encourage a certain kind of professional neglect. So that’s how promising careers of talented young dreamers usually spark, sputter, and die in obscurity.

Karen Berger, the founder and editor of DC’s subsidiary Vertigo Comics, is the reason why Neil Gaiman is a household name. It’s impossible to say whether Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman would’ve ascended to global celebrity without her sponsorship, but she was instrumental in building their careers. Karen Berger was tasked with scouting Great Britain for comics authors and illustrators, and she later shepherded notable franchises and artists such as Bill Willingham’s Fables, Brian K. Vaughn’s Y: The Last Man, Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, Brian Azzarello's 100 Bullets, Mike Carey’s Lucifer, and Garth Ennis’s Preacher. Many of these franchises were later adapted into films, or television series.

The foundation of Vertigo Comics was performed as a defensive maneuver by DC Comics, because they were famous for offering lopsided, unfavorable contracts to comic authors, and the massive commercial, critical, and aesthetic success of an emerging competitor named Image Comics posed an existential threat to their existing business model.

Image comics was established in 1992.

The next year, Vertigo Comics was established in 1993, sparked by fear and extreme reluctance to compensate authors and illustrators according to their commercial leverage.

Personnel is policy.

Alan Moore was hired by DC Comics editor Len Wein to write Swamp Thing in 1983. He later trained Neil Gaiman how to write comics, and then introduced Neil Gaiman to Karen Berger. The history of how their friendship, mentorship, and collaboration developed is recounted in tremendous depth in “The Sandman Companion”, compiled by Hy Bender:

“Alan Moore’s work was so remarkable that it inspired Gaiman, who had ignored comics for years, to start reading them again, and eventually to write comics himself, employing a similar pioneering approach.

Moore’s influence didn’t end there, either. Gaiman is famous for writing very long comic scripts that carefully describe what happens in every panel. There’s only one person in the industry who writes scripts that are even longer.

“Yes,” admits Moore (whose script for the twenty-six page first issue of his classic Watchmen comic ran over a hundred pages), “that bad habit came from me.”

“You’ve got to remember,” Moore quickly adds, “that in my day comics weren’t regarded as being of much importance and publishers weren’t particularly supportive about your work. So when you wrote a script, you’d have no idea who’d be drawing it, or lettering it, or coloring it; which meant there were all sorts of things that could go wrong. My solution was to put into a script every nuance of the images in my head, so it was crystal clear what I was aiming for, down to the finest detail.”

“As it happened,” continues Moore, “that approach got the best results. Artists didn’t feel crushed or restricted by all the description; most of them seemed to enjoy it. Also, I found that by trying to think of every angle of a story from the standpoint of my collaborators, I’d come up with effects that I wouldn’t have otherwise.”

“So when Neil Gaiman asked me, ‘How does one write a comic script?” I showed him how I write a comic script. And that’s what doomed Neil, and everybody who works with him, to these huge, mammoth wedges of paper for every story he does.”

“I’d like to think my main influence was the understanding that it’s quite all right to trust your own ideas and to consider your own perspective valid.”

“In other words,” Moore concludes, “if Neil got anything from me, I hope it was a respect for one’s individual voice; and an insistence on the right to bring that voice to whatever material you’re handling.”

…

Neil Gaiman: “I fell in love with comics again. It was like returning to an old flame and discovering that she was still beautiful. But Alan Moore’s stuff was impressive. He showed what one can really do with comics, that they can be as powerful a vehicle for art as any other medium.”

…

Hy Bender: “During that same period, you became friends with Alan Moore, who — present company excluded — is arguably the finest comics writer in the history of the medium. How did you and Alan first hook up with each other?”

Neil Gaiman: “When my book Ghastly Beyond Belief, which I wrote with Kim Newman, was published in 1985, I sent Alan a copy accompanied by a note that basically said, “You’ve given me enormous amounts of pleasure, I think you’re terrific, and this is something I’ve done. Hope you like it.” Alan called me a week later, and from then on we were phone pals.

…

Hy Bender: “I know that Alan is the one who taught you about writing a comics script. Do you recall how that happened?”

Neil Gaiman: “Oh, certainly. About eight months after we first chatted, I mentioned to Alan that two of his favorite writers, Clive Barker and Ramsey Campbell, were going to be at the British Fantasy Convention at Birmingham. As a result of my journalism work, I knew both Clive and Ramsey, so I told Alan, “Come on down; I’ll look after you and make sure you don’t feel out of place.” And he did, and I did, and we had a great time.

“Toward the end of the day, we were talking about comics, and I said, ‘I don’t understand what a comics script looks like. How do you tell the artist what to draw?’ So he showed me a script’s format, step by step, on a sheet of paper: ‘Put down ‘Page 1 panel 1’ like this, then describe what happens in the panel, then write the name of the first character who talks, then put down his dialogue,’ and so on.”

“After receiving that tutorial, I went home and wrote a short comics script titled, “The Day My Pad Went Mad” based on Alan’s wonderful John Constantine character. In retrospect, the story wasn’t very good, and the ending was wrong. But I sent the script to Alan, and he told me, “Yeah, it’s all right. The ending’s a bit off.” And then he actually used a few lines of my story in Swamp Thing 51, “Home Free”, which was very encouraging to me.

“I next wrote a sixteenth-century Swamp Thing titled “Jack in the Green” and sent it to Alan. When I asked him if it was okay, he said, ‘Yeah, I would’ve been proud to write that.’ That made me very happy.”

…

“September 1986, was the usual UK Comic Art Convention, and Karen Berger was attending it as DC Comics’s liaison to British writers and artists. I walked up to Karen and introduced myself, and she responded, “Oh yes, Alan Moore’s mentioned you.” Taking that as a good sign, I immediately mailed her my Swamp Thing script, “Jack in the Green”.”

“Five months later, after seeing that Alan Moore, Brian Bolland, Dave Gibbons, and other Britishers had worked out really well, DC decided that it wanted the rest of us. In February 1987, Alan called to tell me that Karen was returning to town on a UK talent-hunting expedition. And accompanying her this time would be Dick Giordano, who was DC’s vice president —”

Hy Bender: “Let me interrupt your personal tale a moment to note that DC’s perception was on the money — there was, as it turned out, a great deal of comics talent in the UK, just waiting to be tapped by a shrewd publisher. Why do you think that was the case?”

Neil Gaiman: “Part of it was simply that no one had bothered to come after us before. But a more important reason, in my opinion, is that there was a generation in the UK who’d grown up reading DC Comics from a bizarre perspective. In America, those comics were perceived without irony; in England, they were like postcards from another world. The idea of a place that looked like New York, the idea of fire hydrants and pizzerias, was just as strange to us as the idea that anyone would wear a cape and fly over them.”

“Also, these comics were being read by bright, rebellious kids, and we perceived them as part of a dynamic cultural movement — along with David Bowie and punk rock, Roger Zelazny and the New Wave in science fiction, and stories by William Burroughs.”

Hy Bender: “How did you place yourself and Dave in the sights of DC’s talent hunt?”

Neil Gaiman: “Quite simply, I asked a UK comics friend to give me the name of the hotel where they were staying. I rang them, Dick answered, and I said, “An English comics writer and English comics artist want to come and see you.” And Dick said, “Okay. Thursday, two o’clock.” And to prepare, I wrote a Phantom Stranger plot overnight.”

…

“So Thursday came, and I went with artist Dave McKean. We opened the door, and Karen looked up and said, ‘Neil! I didn’t know it was you we were meeting. I wanted to get in touch anyway, because I read your ‘Jack in the Green’ story on the plane coming over and really liked it.’ Again, a good sign.”

…

Neil Gaiman: “On the train home, I’d already started plotting. The next morning, I phoned Dave McKean and spent literally a half hour telling him the entire story. He loved it, and he went off and did four paintings. Meanwhile, I sat down and wrote a long outline. And we dropped off our completed work at Karen and Dick’s hotel just before they left on Sunday afternoon. Years later, Karen told me that the most important thing for them was the fact that on Thursday they told us to do Black Orchid, and on Sunday they walked away with a detailed outline and these four huge, gorgeous paintings. So that was how Dave and I came to work for DC Comics.”

—Hy Bender, The Sandman Companion

The recruitment, mentorship, promotion, and commercial opportunities that Karen Berger provided to British comics authors and illustrators launched a generation of stars. Even storytellers she didn’t directly coach benefitted, such as Grant Morrison’s protege Mark Millar, who created famous comics such as Wanted, Marvel: Civil War, Ultimates, Kickass, and Jupiter’s Legacy — all of which were later adapted into films or television shows.

Network effects play a crucial role.

This pattern repeats everywhere you look, in any field.

In Hollywood, Francis Ford Coppola mentored and groomed the “New Hollywood” generation of filmmakers, which included George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorcese, Brian DePalma, and Terrence Malick, among others. They dominated Hollywood for decades, and mentored proteges of their own — such as when Steven Spielberg mentored Robert Zemeckis, and helped him raise funding to film Back to the Future. At the time, none of the studios believed that Back to the Future would be a successful franchise.

Likewise, the low-budget director Roger Corman shot more than a hundred films, and was an expert in selling distribution rights to cheap films in order to guarantee profitability. Roger Corman mentored a long roster of directors and actors, including Francis Ford Coppola, Jack Nicholson, James Cameron, Ron Howard, William Shatner, and Peter Bogdanovich.

Walt Disney recruited a group of star animators who later became famous as “Disney’s Nine Old Men”. They were deeply involved in the success of Disney animation between 1937 and the 1970s — but as soon as they retired, Disney animation started to stagnate, and a new echelon of studio executives began to purge and suppress their most talented proteges, motivated by jealousy, fear, self-preservation, and a desire for managerial control. Some of the animators (John Lasseter, Brad Bird) trained by Disney’s Nine Old Men were sent into a sort of artistic exile, spent years in the Hollywood wilderness, and went on to be instrumental in the success of Pixar. Later Disney ended up acquiring Pixar to reinvigorate their own animation division — by hiring the creative visionaries who their executives had pushed out. Firing John Lasseter turned out to be a multibillion-dollar mistake.

Personnel is policy.

The trend I’m getting at here is that global conglomerates like Disney, Paramount, and 20th Century Fox have massive financial resources which theoretically should empower them to interview, hire, develop, and promote the world’s best animators; actors; film directors. But history reveals that excess financial liquidity does not translate to successful management of ambitious personnel. Even in a billion-dollar globalized competition, the intimacy of personal trust and friendship provides prolonged market dominance to the teams of comrades who are able to build each other up.

Their competitors are not playing the same game.

What we are talking about here are secret societies, cartels, conspiracies, cabals. These secret societies are informal networks which converge around a shared vision, a compatible aspirational worldview, and transmit value across beloved friendships of like-minded dreamers with a relentless work ethic and a boundless imagination.

Screenwriter Shane Black comments,

“Shane Black: Getting an agent or manager is essential. It’s the most important thing for a young screenwriter, to have their work made available to the industry by someone with more credibility, so people don’t just toss it when it comes over the transom. For me, it was about getting momentum through this group of friends who I was with in college. We all came up together. One of us would get an agent, and then he would reach down the ladder a rung and help someone else up. Then I would in turn help someone after me, and we’d sorta leapfrog up the ladder, each providing whatever access we could by banding together as a group instead of trying to take on Hollywood one by one. It’s important to find a group of like-minded people who are on the same wavelength, who wanna write screenplays as badly as you do, who aren’t selfish, who support you. If you’re sinking or you’re drowning, it’s nice to have somebody else in the boat.”

—Peter Hanson, Tales from the Script: 50 Hollywood Screenwriters Share Their Stories

Other examples of famous talent networks which achieved abnormal heights of success include the PayPal Mafia, which included billionaires Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. Or the "Traitorous eight" who founded Fairchild Semiconductors in 1957.

In the NFL, Head Coach Mike Shanahan pioneered, refined, and revolutionized an offense schematic inherited from Bill Walsh, based on collected notes available to the 49ers Franchise. Today an outsized percentage of NFL head coaches originate from the Shanahan coaching tree: Kyle Shanahan (49ers), Sean McVay (Rams), Matt LaFleur (Packers), Mike McDaniel (Dolphins), Robert Saleh (Jets), Zac Taylor (Bengals), DeMeco Ryans (Texans), and Kevin O’Connell (Vikings).

Success breeds success.

Friends compete against, educate, and sharpen their friends.

One question is: How can we replicate the British miracle? How can we build a secret society, an artistic cabal, a friendly conspiracy of dreamers who will push and encourage each other to develop a marvelous, gorgeous aesthetic movement?

I would argue that FrogTwitter represents the embryonic architecture of a similar conspiracy of friends.

So far, Lomez and Raw Egg Nationalist have filled a similar role in the creative ecosystem that Karen Berger performed at DC Comics. Passage Publishing, and Mansworld Magazine, have been tremendous in encouraging, developing, promoting, and publishing the work of talented young storytellers who demonstrate exhilarating potential.

Friendships naturally form in the aftermath, which fuels additional imaginative products. It’s important to realize how rare this is; how special; how powerful.

Hollywood studios and New York publishers are too impatient, myopic, and nepotistic to invest in their own minor leagues farm system, but they are unable to compete against the premium quality of a thriving talent pipeline.

Cross-pollination between artists is a miraculous accelerant.

TR: Question 3. Adaptation and supplemental material. There is a great short video called “Saturday Morning Watchmen” as well as a Simpsons Episode where Alan Moore is asked to sign a copy of “Watchmen Babies: V for Vacation”. No one has been able to adapt this material or add to the “universe” as well as Moore and I think Moore did this on purpose because he puts the “tank” in cantankerous. There are plenty of smart (and not so smart) people who have tried to adapt Watchmen and failed. Can you speak on why that is?

BP: This is a tough question, and definitely the toughest question you’ve asked me.

How to adapt, and expand a classic.

We might formulate the question as, “If Watchmen is a masterpiece, why has nobody been able to make a good film out of the comic?”

And we might formulate the follow-up question as, “What was special about the original twelve-issue miniseries Watchmen, which the sequels, expansions, prequels, and spin-offs of Watchmen are lacking?”

The follow-up is an easy question to answer: Watchmen’s spin-offs have consistently failed, or disappointed, because they copied the superficial aspects of the twelve-issue Watchmen miniseries, while overlooking, ignoring, and avoiding the foundational design principles that made Watchmen a masterpiece.

Peter Thiel explains why imitation doesn’t guarantee quality, in his book Zero to One:

“Every moment in business happens only once. The next Bill Gates will not build an operating system. The next Larry Page or Sergey Brin won’t make a search engine. And the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t create a social network. If you are copying these guys, you aren’t learning from them.

…

The paradox of teaching entrepreneurship is that such a formula necessarily cannot exist; because every innovation is new and unique, no authority can prescribe in concrete terms how to be innovative. Indeed, the single most powerful pattern I have noticed is that successful people find value in unexpected places, and they do this by thinking about business from first principles instead of formulas.”

—Peter Thiel, Zero to One

In 2012, DC Comics released an Event comic book of nine interconnected miniseries set in the world of Watchmen, a collection of overlapping prequels which take place before Alan Moore’s Watchmen, and expand the backstory of his characters. These intertwined prequels were branded as “Before Watchmen”.

The Before Watchmen comics were okay, I suppose, but I’m kind of forced to ask the question whether they bothered reading the original source material. One of the main themes of Alan Moore’s Watchmen was the bittersweet emptiness of nostalgia, and how sentimental reminders of the past fail to correct for contemporary dysfunction.

I never bothered to watch the HBO Watchmen series, for several reasons. The costumes, cinematography, and visual aesthetic were decent, but the show’s promotional trailers focused on Black race relations, Civil Rights, and the Klu Klux Klan. None of that has anything to do with Alan Moore’s twelve-issue miniseries. It appeared to be joyless propaganda; fake and ghey.

The expansions and spinoffs to Watchmen have mostly been formulaic fan service applied to the beloved characters of Alan Moore’s original miniseries. There’s a lack of scope and ambition, in regards to carrying on the aesthetic philosophy which birthed Watchmen, or imitating the laborious, meticulous, and time-intensive mechanical process which Alan Moore developed to craft his story.

If I were running DC Comics, I would assemble a 700-page pdf of Alan Moore’s interviews, write up chapter summaries of the storytelling lessons contained in each interview, append the summaries to the each dialogue segment, then print this compendium into leather-bound handbooks used to train all their comics authors. It seems like an obvious mistake to ignore Alan Moore’s insights.

One rudimentary question is to ask: What made Watchmen special? What was the value proposition of this series?

In a 2009 interview, Alan Moore commented about the artistic futility of adapting his source material into a film:

“It’s a completely pointless idea, because Watchmen, at least in my mind, wasn’t about a bunch of slightly dark superheroes in a slightly dark version of our modern world. It was about the storytelling techniques and the way that me and Dave were altering the range of what it was possible to do in comics; this new way that we’d stumbled upon of telling a comic book story. The plot was more or less incidental. All of its elements were properly considered, but it’s not the fact that Watchmen told a dark story about a few superheroes that makes it a book that is still read and remembered today. It’s the fact that it was ingeniously told and made ingenious use of the comic strip medium. From everything I’ve heard, the director belatedly realised that, no, he couldn’t handle the Black Freighter narrative in the film, because that’s an example of me doing something that can only be done in a comic. He also realised he couldn’t include the back-up material. Apparently, they’re releasing animations of The Black Freighter and Under the Hood separately. Now, I’m sure that’s terribly clever, but I can’t help think that me and Dave were able to make this as one coherent package twenty-five years ago, using eight sheets of folded paper and some ink. It was a completely thought through, coherent package in its most perfect realisable form.

Sure, I’ve heard it’s great seeing Dave Gibbons’s images reproduced on the big screen. “They’re exactly the same as in the comic, but they’re bigger, moving, and making noise!” Well, putting it cruelly, I guess it’s good that there’s a children’s version for those who couldn’t manage to follow a superhero comic from the 1980s.”

—Alan Moore

Only in the most superficial sense are DC Comics writers imitating Alan Moore when they use the characters he created. Because nobody wants to do the exhausting amount of work necessary to create a multifaceted, layered, branching narrative with the same level of complexity as the original franchise.

If a new, up-and-coming author was capable of writing a masterpiece with the same level of technical complexity, meticulous planning, and nested framing, something of the same ambition, scope, depth, texture, ambiguity, and drama of Watchmen — the smart move would be to create a new franchise, completely disconnected from Alan Moore’s world, free from the burden of expectations that are inevitably linked to what many consider to be “the best comic of all time”.

In 1985, Alan Moore enthusiastically discussed a plan to create a twelve-issue prequel to Watchmen, a franchise of the same complexity and ambition as Watchmen, starring the Golden Age superheroes of a previous age. The series was suggested under the title of “Minutemen”.

Unfortunately, his relationship with DC Comics fractured soon after, and the proposed franchise was never written.

Alan Moore had a financial dispute with DC Comics in 1989, after the massive commercial success of Watchmen. He realized he was being cheated, and that DC Comics was violating the terms of their contract, but that he had no legal recourse, and DC Comics was too shortsighted to fairly reward Alan Moore for his creations under their corporate umbrella. DC Comics only paid Alan Moore 2% of the profits from Watchmen, they violated their merchandising clause so that Watchmen merchandise was reclassified as “promotional items” in order to prevent paying Alan Moore the profits he was owed, and additionally, DC Comics exploited a loophole in their contract to prevent legal ownership of the Watchmen franchise from reverting to Alan Moore.

(Specifically, the deal specified that when Watchmen went out of print, the rights would revert to Alan Moore. So DC Comics always maintained at least a small, bare minimum print run of Watchmen to retain ownership of the franchise.)

This has been a consistent problem with DC Comics throughout the life of their company, that they deceive, defraud, and exhaust the creative talent who invent their most popular stories, and bestselling comics. Anyone who signs a contract with DC Comics should realize they are collaborating with a dishonest, manipulative, evasive partner before the relationship begins. DC Comics has been involved in bitter, vicious, prolonged fights with their best talent for nearly a hundred years — so cheating employees is embedded deep in their corporate culture.

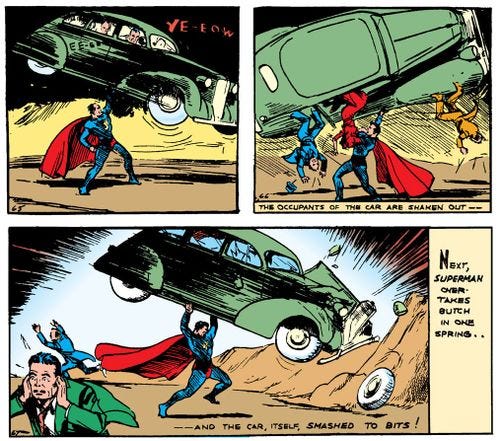

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster invented Superman in 1938, largely imitating the pulp fiction hero Doc Savage (the Man of Bronze), and this character pioneered the superhero genre. In 1947, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster sued DC Comics for various intellectual property disputes, DC Comics settled with them, and then DC Comics immediately fired them. Twelve years later, in 1959, DC Comics rehired Jerry Siegel. In 1965, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster sued again over a new set of intellectual property disputes, and after the lawsuit concluded, DC Comics fired Jerry Siegel again. Lawsuits and public disputes continued intermittently until 2010 with the Shuster and Siegel family heirs.

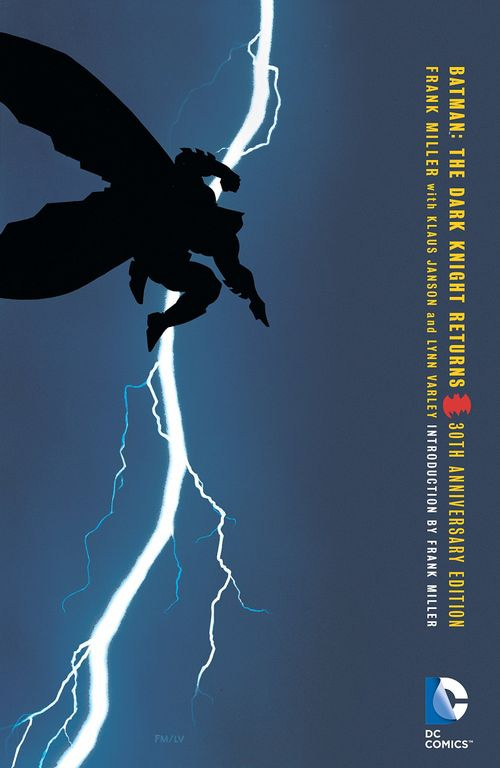

Frank Miller, the bestselling author and illustrator (famous for Sin City, Daredevil, The 300, Ronin, and the creation of Elektra) discovered in 2021 that one of his editors at DC Comics had stolen original cover art for the Dark Knight Returns — which was a cheap internal work product when Frank Miller created it in 1986, but appreciated in value after the massive commercial; critical; cultural success of The Dark Knight Returns. The artwork was valued in 2021 between two million and three million dollars. Frank Miller’s editor David Anthony Kraft pretended he had lost the artwork, while keeping it for himself. Frank Miller discovered he had been cheated when Kraft’s widow uploaded the artwork to an online auction in 2021, and he sued for ownership of the stolen artwork.

More recently, on September 14th, 2023, comics author Bill Willingham announced that he was sending the popular DC Comics franchise Fables into the public domain. This was designed as a legal Pyrrhic victory, to destroy the financial value of the comic franchise. In a long series of updates and clarifications, Bill Willingham explained that DC Comics had repeatedly violated contractual obligations to him, including “accidentally forgetting” to pay him more than $60,000 of royalties — until he caught their embezzlement with a forensic audit.

Willingham Sends Fables Into the Public Domain

So there’s an ongoing pattern of deceit, intransigence, and legalistic harassment.

These are just a handful of examples, which are publicly available. Behind the scenes, intense bullying, dysfunction, and exploitation rages.

And this is how they treat their best talent, who are proven winners, who create massive bestsellers which fuel the success of global franchises.